RESEARCH AREAS

The MALMECC project coalesces a number of sub-projects, which together aim to cover many different aspects of medieval music making in the context of courtly culture.

Click the links below to find out more:

Laura Slater (project member 2016-2019 - see blog 'Meet the Researchers') is researching the cultural patronage of Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III of England. Originating from a region that now cuts across northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands, Philippa’s importance as a transnational cultural patron is well-known. A manuscript associated with her marriage re-sited two French polyphonic motets into an English context. The poet-musician Jehan de la Mote dedicated his c.1339 verse lament on the death of Philippa’s father, Count William of Hainault, Holland and Zeeland to the queen. He may even have performed at the English court. The chivalric chronicler Jean Froissart called himself ‘one of her clerics and familiares [an intimate, part of the queen’s trusted inner circle]’, priding himself on his place in her household from around 1361. Philippa even commissioned her own tomb effigy from overseas, hiring Jean de Liège, a Brabançon working at the Valois court of France in the 1360s to make the grand monument seen in Westminster Abbey today.

Yet the manuscripts associated with Philippa’s ownership and personal devotional use have never been explored in detail. Among several surviving manuscripts made to mark the accession of Edward III and his marriage is a very small psalter made in the later 1320s, possibly as a wedding gift for Philippa. ‘Marital manuscripts’ of this type were designed to act as a spiritual primer for married life. Philippa’s psalter would have been required to provide spiritual support and guidance to her in particularly difficult circumstances. Aged anywhere between ten and fifteen, Philippa landed in England in December 1327, barely a week after the funeral of her deposed and murdered father-in-law, Edward II. She found her new husband to be the increasingly unwilling puppet of a regency government dominated by his mother, Queen Isabella of France, and her possible paramour, the English nobleman Roger Mortimer. Philippa spent her first three years in England completely overshadowed.

The second manuscript, perhaps made c. 1340, dates to happier times. A much larger and grander psalter now in the British Library, the ‘Psalter of Queen Philippa’ contains musical notation throughout. This is extremely unusual for a manuscript made for a lay user. Philippa is known to have been close to the clerics in her household: the Queen’s College, Oxford was founded in her honour by one of her chaplains, Robert de Eglesfield. Laura is exploring how the visual representation of sound in the pages of the psalter might have influenced the queen’s devotions. She is considering the different ways and contexts in which Philippa may have used her psalter, in places such as St Stephen’s Westminster or St George’s Windsor. And she is investigating what we can learn from the manuscript and other sources about Philippa’s musical and intellectual interests.

See her introductory film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dhSwibfboIE&feature=emb_logo

Here is a link to her current post: Dr Laura Slater MA, PhD | Department of History of Art (cam.ac.uk)

Who was a medieval cardinal? How did he behave? And how did he react when the Church was torn apart by a Schism? To answer these questions, and much more, Christophe Masson (project member 2016-2019 - please see blog post 'Meet the Researcher') explores the identity and organisation of the courts held by cardinals who lived in Avignon during the first period of the Great Western Schism (1378-1403) when two popes competed, one living in Rome, the other in Avignon.

This project combines three main objectives. First, it challenges the idea of a static community of princes of the Church and of cardinals who acted only as ministers or ambassadors for the pope. During the Schism, their role was being redesigned, and they tried to influence, if not to govern, the pope they followed. One of the cardinals’ main weapons were their courts, where they acted as art patrons and political intermediaries, often supporting claims from lay princes as well as their own interests. This evolution made them, amongst other things, able to challenge the pope’s alleged central role in cultural exchanges and politics.

Image Copyright - Jean Marc Rosier

Secondly, Christophe's project enlightens the seigniorial aspects of cardinals’ courts and behaviours by combining a multimedia approach—including palace decoration, building of tombs, musical and reading practices— with a study of performativity (conduct of masses and ceremonies, including funerals). This is made possible thanks to the transdisciplinary composition of the MALMECC team which combines art history, musicology, literature, and history. The cultural choices of the cardinals will be used to demonstrate how late medieval cultural practices contributed to establishing, or defending political power and influence. Cardinals’ courts will thus be investigated as groups able to produce their own original (micro-)culture—a mix of papal, ecclesiastical, familial, princely, and noble—that cannot be equalled a priori to the ones of lay or ecclesiastical princes.

The last point of focus of Christophe's project is that of regional origins of the courtiers surrounding the cardinals. Popularized by the writings of Church reformers, the idea that the Avignon Papacy grew out of the appropriation of the wealth of local churches still permeates lots of modern publications. This prevents us from understanding the mutual, although unbalanced, interests that linked a cardinal and the places he held benefices in. Since the prelate was attracting large amounts of money, local clerics were keen to aggregate themselves around his court. It was a way for them to claw back a part of the revenue that was produced in their home region, through their pensions and salaries, but also, more importantly, for bishops and abbots to have a spokesperson in the very heart of the Christendom. All of these clerics were key actors within the transnational cultural model of Avignon cardinals’ courts.

Ultimately, the research leads to a reconsideration of cardinals’ position in the government of the late medieval Catholic Church, removing them from the shadow of the Popes and, instead, considering them as princes of the Church in their own right. For many of them, being theoretically at the periphery proved an ideal position to act decisively on the centre, i.e., the Pope himself.

See his introductory film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aWUkYOi-hkw&feature=emb_logo

Christophe's current post is described here: Fiche annuaire MASSON Christophe (uliege.be)

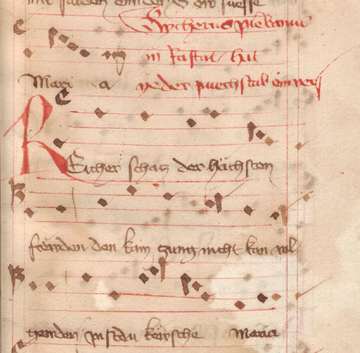

David Murray (project member 2016-2019 - please see blog post 'Meet the Researchers') investigates the archiepiscopal court of Salzburg. There, the anonymous ‘Monk of Salzburg’—among other courtiers—composed one of the most important collections of songs in German in the fourteenth century. Including both spiritual and secular material, they offer a fascinating insight into the cultural activity surrounding Pilgrim II von Puchheim, Archbishop of Salzburg between 1365-1396. The project asks what made Salzburg so fruitful, and what it can reveal about the traditions of song that sounded around the court of a later medieval Prince of the Church.

Where previous scholarship has focused on individual parts of the song corpus attributed to the Monk, most notably treating the sacred and profane elements separately, David is approaching the corpus as a connected, though not necessarily unitary, whole. The two sides must be held together if one is to gain a proper grasp on the nature of song at the ecclesiastical court, which by its very nature, and particularly in the case of a figure such as Pilgrim, brings together aspects of both worlds. This stance also relates to the way he tries to deal with medieval song, as a phenomenon which is more than the sum of its constituent parts (words, music, metrics), an attitude David has been exploring in the context of the Marian sequences in the corpus. Here, not only in the pieces the Monk translated from the Latin into German, but also in the Monk’s own compositions and contrafacta, the interplay of verbal and melodic components are essential to their full worth and resonance, and therefore to their Sitz im Leben.

The interest in the function and place of the Monk’s songs also informs David’s engagement with the secular songs. What role did the act of composing these songs have in the circle of Archbishop Pilgrim, a political animal on a European scale? What might they suggest about the nature of his court, and how can they be situated in the network of cultural influences from and engagements with the ecclesiastical and profane potentates and institutions with which Salzburg maintained relations in the fourteenth century? What evidence can be found among the subsequent transmission of the Monk’s songs (particularly at universities and religious houses) for their earliest days? Using a combination of literary historical study and the examination of the Monk’s musical legacy along with the evidence of archival sources, David’s monograph study will offer a holistic account of the culture of song and poetry that came into being around Archbishop Pilgrim.

See his introductory film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FArz3MZd7DY&feature=emb_logo

Karl Kügle (Principal Investigator) researches the role of clerics at courts of the long fourteenth century, with a focus on Savoy, Cyprus and northern Italy. The lifetime of Amadeus VIII (b. 1383, d. 1451) is without doubt one of the high points of Savoyard cultural history. During his reign, Savoy was raised from county to duchy by Emperor Sigismund (1416). The wedding of Amadeus’s son Louis to Anne, princess of Cyprus and Jerusalem, in 1434, became an instant legend in its time, and united the most brilliant courtiers of Europe and their artistic retinue in Chambéry. Guillaume Du Fay, one of the most important musicians of the fifteenth century, was associated with Savoy from 1434 well into the 1450s. When Duchess Anne purchased the shroud of Turin (1453), an important Mass may have been composed by Du Fay for the liturgy associated with the shroud. Amadeus’s own career took two unusual turns when he withdrew from government (1434) to live in spiritual retirement on the shores of Lake Geneva and later accepted the papal see offered him by the Council of Basle (1439-49). He ended his life as a cardinal (1449-51).

Such an unusual biography, criss-crossing noble and clerical status in a single individual, raises a more general question: What was the role of clerics in courtly life? Distinguished by their status from the courtiers-at-large, who were lay persons, clerics seemingly stood aside from the courtly game of perpetuating their family's lineage and power through marriage but at the same time exerted powerful social and political roles precisely through their 'neutral', clerical status. Clerics' roles at court were highly diverse, and largely contingent on their own social background and lineage, ranging from influential figures such as confessors to cogs in the wheels of courtly administrations to scientific and political experts consulted by the most powerful princes for advice in highly charged questions such as the position of the realm during the Schism. For aristocratic women, joining a convent or an abbey, often at widowhood, could be an expedient means to retain a measure of independence combined with a considerable quantity of social capital. Court chaplains included some of the best known singers and composers, but also as poets, tutors of noble children, administrators, and propagandists. Higher-level clerics at court were canons of major cathedrals and collegiate churches, providing another interface between the Church and the court, and bishops and archbishops functioned ex-officio as peers of the realm, taking the roles of functioning senior political advisers, diplomats, power brokers, and confidantes not just to the ruler but also to the nobles surrounding him (or her) and their often very extended family. Clerics also enjoyed their own quasi-courtly societies in universities, cathedral and collegiate chapters, and even monastic settings; while some of them enjoyed lightning careers due to their noble birth, others rose from undistinguished backgrounds to positions of great prominence. As the best educated social group of their time, their impact on late medieval culture cannot be overstated.

Most importantly for the MALMECC project, many of them kept courts of their own (usually called 'familia'). These 'familiae' often were important informal nodes of intellectual and cultural life, making them somewhat comparable to the salons of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Karl's research focuses on a number of case studies that explore the interface of clerics as courtiers with princes and other clerics (and their courts or communities) in the long fourteenth century. Taking musical artefacts as his cue, he explores the complex roles of courtiers like Philippe de Vitry, Guillaume de Machaut, Jehan Froissart, Pietro Filargo (Peter of Candia), or Martin le Franc in the complex, trans-national networks linking courtly and ecclesiastic societies.

See his introductory film here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FArz3MZd7DY&feature=emb_logo

David Catalunya (project member since 2019) studies court culture at the Royal Abbey of Las Huelgas in Burgos (Spain) in the period 1200–1360. Las Huelgas occupies a prominent place in the history of Western music. Its monastic library preserves a famous manuscript of polyphonic music from the fourteenth century, known as the Las Huelgas Codex, which has long attracted the attention of musicologists, performers and the general public. Far from being confined solely to the monastic sphere, however, the nuns of Las Huelgas were often involved in affairs of state and participated actively in the communication of power. While art historians acknowledge the abbey as a truly remarkable architectural ensemble that combines Arabic, Romanesque and Gothic traditions, Hispanist historians primarily see it as a lieu de memoire for the royal dynasty of Castile as well as a chief site for political and courtly intrigue.

Queen Berenguela at Las Huelgas. Cantigas de Santa Maria, Biblioteca del Escorial. (C) Patrimonio Nacional

Las Huelgas was the place regularly chosen by the Castilian monarchy to perform the most extravagant royal ceremonies, and the nuns themselves co-officiated public events such as coronation masses. As a major stage for the exhibition of power and for political propaganda, the abbey was placed among the wealthiest and most prestigious institutions in the entire kingdom. As such, it enjoyed many special privileges as well as an extraordinary institutional independence, even from the Cistercian Order, to which the abbey only symbolically belonged. The princesses who inhabited and governed Las Huelgas built their own palaces inside the monastic complex, and their entourages included not only clerics and chaplains, but also Muslim ‘officials’ who lived inside the monastery. In fact, many elements in the building reveal a markedly courtly visual culture within the monastic setting.

Grantley McDonald (project member since 2019) explores music at the court of Frederick (1415-1493), Duke of Styria from 1424, Duke of Austria from 1439, elected German King in 1440, and crowned Emperor 1452. Long seen as an unsuccessful ruler, Frederick is increasingly recognized by historians as a pivotal figure: not only was he the longest-ruling of all Holy Roman Emperors, but he also was responsible for a shift in the balance of power in the Empire toward the southeastern periphery (present-day Austria) that was to be felt for centuries. He engineered the acquisition of the Burgundian territories for the house of Habsburg by marrying his son Maximilian to Mary, the daughter of the fourth and last Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold (1477). He also established the Habsburg claim to the throne of Hungary (1491).

Historians took a dim view of the cultural accomplishments of Frederick’s court up to now, but new research suggests that this view, too, is ripe for re-assessment. The presence of singers from the prince-bishopric of Liège at Frederick’s court has long been known but never been explained. Comparatively little is known about literary life at Frederick’s court, although his marriage with the Portuguese princess Eleanor (1452) bespeaks a transnational outlook. Frederick’s activities as a patron of architecture are impressive; his residence in Wiener Neustadt was deliberately set in contrast to the re-building of Prague by his Luxembourg predecessor, Charles IV. Frederick’s motto a-e-i-o-u and his keen interest in astrology add a further twist to this underrated and poorly understood ruler.

Uri Smilansky (project member since 2019) is investigating the relationship between musical visuality and social value in Francophone and Francophile courts. He explores the encoded meanings discernible in the visual inclusion, presentation or exclusion of music on manuscript pages as they interact with courtly and cultural politics, from the point of view of patrons and of practicing professional musicians from the generation of musicians, c. 1350-1425.

Increasingly depending on highly trained musicians but still including courtiers themselves, performances of music and, more generally, soundscapes at court resulted in an additional level of economic activity beyond the creation and circulation of material artefacts and the demonstration of cultural capital by patrons. Within each sphere, how is this tension between exclusivity and exposure resolved? To what degree did different kinds of circulation assist or hinder this balance? With this tension in mind, what agency could various types of music claim on the pan-European political stage? This sub-project takes a systematic approach to late medieval European court cultures and aims to unpack a number of circulation layers with the pan-European system of 'courtliness', assessing both practicalities and notions of value as they pertain to performers, objects, collectors, courtly (sub-)communities, and patrons.