BLOGS

Over the course of the project, the researchers, guests and the PI have contributed many blogposts to share. Click the titles below to read more about a variety of topics, including featured visits on location, focus themes and the experience of working on MALMECC.

Blogs 12 2019 - 12 2022

Does meaning atrophy or accumulate? A virtual étrenne

Boy, what a year!

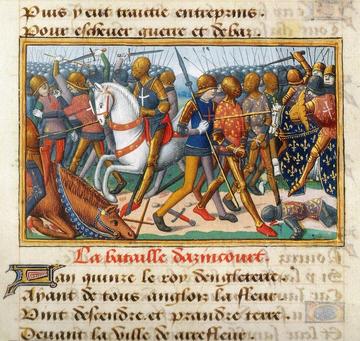

You know you’re in trouble once Machaut’s description of the Black Death, in the prologue to his Jugement dou Roy de Navarre, starts doing the rounds on social media. Cancelled research trips; delayed conferences; trying to find a quiet corner in which to do some work within a locked-down household while maintaining sanity in isolation; and then there is the rest of life… At least we didn’t have to bury our cheese. Terrible segues aside—and yes, that was a link between the current pandemic, that which raged across Europe from 1346 to 1353, and Samuel Pepys’ famous set of priorities when faced with the encroaching flames of the Great Fire of London in 1666—I hope you will join me in raising a glass, whatever time it is when you read this (there must be some advantages to working from home!): To better times ahead, to the survival of the higher education sector, to humanities departments and research funding, as well as to collective and personal health, safety and wellbeing.

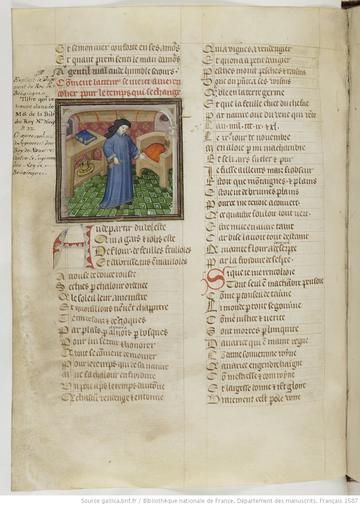

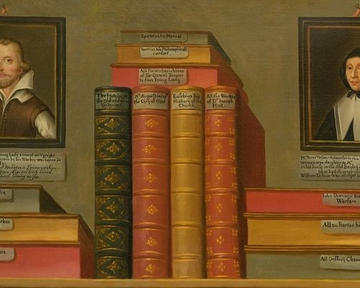

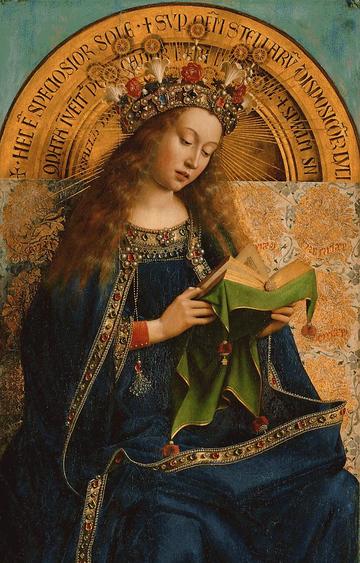

And so, back to Machaut and Pepys. I have long been fascinated by the presence of the former’s Remède de Fortune in the latter’s book collection, a fact that in itself raises both ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. I won’t be discussing the original creation of the manuscript Cambridge, Magdalene College MS 1594 (Machaut manuscript Pe), or the route through which it found its way into Pepys’ hands (although I may be able to offer some new information concerning both aspects soon). Rather, I bring up this example as an illustration of the vicissitudes and fluctuations of meaning and value. It is clear that the Remède did not mean the same thing at its original presentation as it did for Pepys when he purchased his manuscript centuries later. Scholarship traditionally associates the origins of the Remède and its earliest and most luxurious copy (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, fonds français 1586) with the needs and interests of royalty, be they those of Machaut’s direct employer at the time (John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia) or those of the dit’s supposed dedicatee (John’s daughter, Bonne, then queen of France in waiting). Such resonances, however, seem entirely absent from Pepys’ evaluation of his copy of the Remède. It seems that many of his medieval acquisitions had at their core a visual rather than a textual fascination. Beyond the appeal of decorative or illuminated manuscripts (here, his medieval sketchbook, MS 1916, stands out), Pepys was deeply invested in calligraphy. In 1700, for example, he created his first of three scrapbook albums (MSS 2891-3) under the descriptive title: “My Calligraphical Collection, vol. I: Comprehending as well Original Proofs of the Hand-writings of the Ancients in Several Ages within the last 1000 Years; and the Competition for Mastery between Librarians and Printers, upon the first breaking-out of the Latter as the Performances of all the Celebrated Masters of the Penn (now Extant and Recoverable) whether Domestick or Forreign, by Hand or Burin, within the last and praesent Age.” It seems likely that the appeal of what became Cambridge, Magdalene College MS 1594 was related to this interest, it being a pleasing example of an antiquated script, with the added bonus of an illumination on fol. 12v. This view suggests that the dit itself held no artistic or content-related value to Pepys at the point of purchase. In trying to draw a line between an initial highpoint of social prestige assigned both to the dit and the book that contained it, and this late seventeenth-century nadir of appreciation, it is possible to point at a more or less gradual loss of musical and visual impact and a declining interest in the subject matter as indicators of an inexorable process of atrophy. Before succumbing to this metaphor, however, we should note that this process was neither linear, one-directional, nor continuous. Indeed, this very blog—along with new editions and translations, dedicated scholarship and repeated performances and recordings—testifies to the Remède’s phoenix-like re-ascendance as an object of interest – and to some, indeed, as an object of admiration. This process relies on a re-accumulation of knowledge and, resulting from it, of interest, and on the referencing of new readings to older ones within a (modern) tradition of interpretation. Putting it perhaps a little more flippantly, and with no stronger claim to linearity or continuity than with the atrophy metaphor, one might say that the resurgence of the Remède’s cultural and artistic value over the 340 or so years since the moment when Pepys bought his copy was as dramatic as its decline over its first 340 years of existence. Actually, we are not certain that the Remède was composed in 1340, nor that Pepys’ purchase took place in 1680 … but both are as good a guess as any other. And, in all honesty, I simply could not resist the round numbers and numerical symmetry built into this chronology while writing this, still in 2020.

I’ll be saying more on the matter soon, but for now, I hand you, my dear readers, over to 2021. Merry Mid-winter, however you choose to celebrate (or ignore) it, and a happy new year, assuming you at least pay lip-service, if not adhere to the Gregorian Calendar.

Uri Smilansky

With suitcases packed

The research project I have been talking about in my previous posts (La Obra Musical Renacentista) has now come to an end. As usually happens in research, it has left us with new hypotheses and objectives that we hope to take on board in the next research project of the Contrapunto team (www.contrapunto.uva.es). Taking advantage of the end of the project, which also coincides with the end of my sabbatical year, I would like to tell you about some of my experiences and impressions at Oxford.

After 27 years as a lecturer and researcher in Spanish universities, being able to enjoy a sabbatical year in Oxford awoke in me expectations that were both, shall we say, extensive and intense. As a researcher and coordinator of research teams, and before taking on any new projects, I wanted to share my experiences with colleagues and teams in the vanguard of international musicology. In this sense, Oxford and its university, as well as the MALMECC project in particular, have turned out to be extremely enriching.

Oxford is a highly evocative city. It is vibrant with knowledge looking to be shared and transferred through a myriad of seminars, conferences, and informal meetings. I will mention just one example: the Seminars in Medieval and Renaissance Music convened by Margaret Bent; they are essential occurrences during term time that enable colleagues in the field to get together for very fruitful meetings.

My collaboration with MALMECC, too, satisfied all my aspirations. MALMECC shares fundamental objectives with La Obra Musical Renacentista and, by extension, with the Contrapunto team and with my own research agenda. Both projects are interested in examining ‘other’ sources, environments, and types of music that are seldom visited in general music historiography. Both challenge established scholarly practice by using and reconciling diverse methodological frameworks when tackling the object of study. What is more, and an aspect which is really vital, both address culture in general, not just music; one at the end of the Middle Ages and the other at the start of the modern period. This has brought about a fluid exchange of information, theorizing methodological frameworks and strategies, between the MALMECC team and myself.

My personal involvement with the MALMECC project began at the conference that the MALMECC team organized in September 2019, Music and Late Medieval European Court Cultures. My presentation was about the symbolic courtly song Nunca fue pena mayor as an example of European emotive intertextuality. I continued working on this song and others in Oxford, which will soon give rise to two articles - which are now merely waiting for the relaxation of library restrictions following the Covid-19 outbreak which will once more permit me access to a few items of secondary literature that still need to be consulted.

CC BY NC SA http://www.museibologna.it

The most enriching aspect of my collaboration with the MALMECC team came about in their periodical seminars in which I met up with the group of inspiring researchers who are part of the project or collaborate with it. It is a multidisciplinary team of musicologists, art historians, general historians, and literature historians interested in recognizing the ‘other’ courts, their creations and interrelations. I recall that in one of these seminars, while Uri Smilansky was presenting his work, the serene expressions on the faces of the Bolognese students of Giovanni da Legnano as depicted on their teacher’s tomb came to my mind, and how different that was from our vibrant and lively seminar debate. It is undoubtedly true that we take away knowledge, but we also take away many enriching experiences.

I would not like to finish without emphasizing the rich musical life of the city of Oxford, something which has both satisfied my spirit and left me wanting more. One thing that has attracted my particular attention is the great sensibility towards music that many, many people here possess (or at least those with whom I came into contact), in a city where I have lived as a researcher but also as a mother of three children attending school.

In conclusion, I can sincerely attest that I leave the University of Oxford with my suitcase full of new knowledge and ideas for new projects, and with the firm resolution to keep up the links created during my stay for a long time to come - despite having had to cope unexpectedly with the COVID-19 pandemic, an extraordinary and distressing situation that has only slightly lessened the intensity of the experience of having worked there for an unforgettable academic year.

Soterraña Aguirre Rincón

Profesora Titular in Musicology

University of Valladolid (Spain)

The Discovery of a Palace for Music (Blog III of IV)

Soterraña Aguirre Rincón

‘Ca en la vihuela es la mas perfecta y profunda musica, la mas dulce y suaue consonantia, la que mas applaze al oydo …. la de mayor efficacia, que mas mueue y enciende los animos de los que oyen [sig. A v verso]’.[1]

This important passage of text extols the affection and desire to listen incited in those who hear the music of the vihuela player. It is found in the opening statement of the LIBRO DE MVSICA / DE VIHVELA INTITVLADO SILVA / de sirenas, a text by Enríquez de Valderrábano that was printed in Valladolid in 1547. The volume contains 169 compositions divided into seven books. Some are new creations, while many others are adaptations for the vihuela of pieces by, among others, Josquin, Gombert, Jaquet de Mantua, or Willaert. The collection also contains pieces by Spanish composers such as Cristóbal de Morales, Juan Vásquez, or Mateo Flecha el Viejo. Silva de Sirenas is dedicated to the fourth Count of Miranda del Castañar, D. Francisco de Zúñiga y Avellaneda.

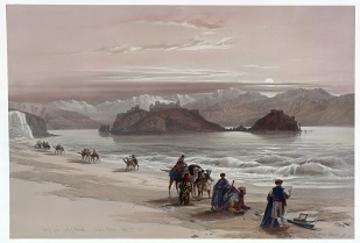

Musician with string instrument. Palacio de Peñaranda de Duero (Spain). Estudio musical. Fresco. CC BY Soterraña Aguirre Rincón NC SA

The music theorist Juan Bermudo (ca. 1510-ca. 1565) also - strikingly - dedicated his Declaración de Instrumentos musicales to the very same person, doing so because of ‘la afficion que tiene [V.S.] a la buena musica, y el saber entenderla, y exercitarla [Prologo, fol. iij verso]’.[2]

Any attempt to write the biography of this important patron has the enormous disadvantage that there is very little documentation about him. However, as luck would have it, we do have access to an exceptional source of knowledge concerning him. By that I mean his Renaissance palace in Peñaranda de Duero, now a small, charming Castilian town in the Duero valley.

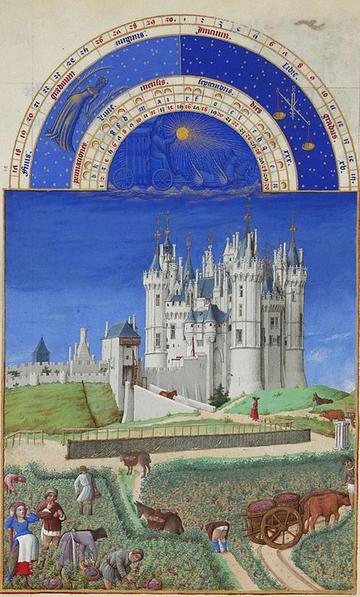

Our project La Obra Musical Renacentista allowed us to experience there the performance of several pieces that we had previously selected for a comparative study. The experience was both thrilling and fruitful - it was a privilege to be able to experience such a place, conceived for the purpose of enjoying music.

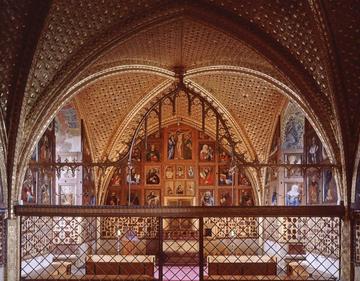

The palace possesses two exceptional spaces designed for musical performances. One is a small room that historiographers, until now, considered to be a kind of gallery where the women ‘could see and hear without being seen’, as it opens to the principal hall of the palace, now called the Salón de Embajadores or ‘Ambassadors’ Hall’. However, its architectural characteristics, the socio-cultural context of its use, as well as certain acoustic qualities of the space that we measured, allowed us to state that its primary purpose appears to have been to facilitate an acousmatic listening experience for those present in the Salón. The small room can accommodate just two or three musicians; its walls are rough, and unpolished. It is located above the lintel of one of the side doors of the Salón, and is 2.84 meters long, 2 meters high and 0.95 meters wide. Unlike a balcony for minstrels, it does not protrude into the Salón. Those present in the chamber cannot be seen from the Salón but goings-on in the Salón can be followed and observed from the chamber. We therefore believe that it functioned in ways comparable to today’s sound systems, providing ‘atmospheric’ music for those congregating in the Salón without them seeing the performers, something which is highly exceptional at this period in history.

The second space is a studiolo, richly decorated with frescoes dedicated to music and musicians. The musicians appear playing numerous different combinations of instruments in realistic poses, both getting ready for playing and while playing their instruments.

These spaces constitute one of the main foci of our next research project. Meanwhile, if you would like to have further information and to see some images, they are available in: Soterraña Aguirre-Rincón and Ana López Suero, “Música, espacios y mecenas. El palacio de los Condes de Miranda en Peñaranda de Duero (c.1510 - c.1550)”, Biblioteca: estudio e investigación (2017) 32: 119-138.

[1]‘There exists in the vihuela the most perfect and profound music, the sweetest and softest consonance, that gives the greatest pleasure to the ear… the most effective, that most moves and fires the mood of those who hear it’.

[2] ‘The liking you [Serene Highness] have for good music, and the understanding of it, and the practice of it’.

Re-visiting the concept of the ‘musical work.’ Part II (Blog 2 of 4)

Soterraña Aguirre Rincón

As I mentioned in my previous post, the research project The Renaissance Musical Work: Fundamentals, Repertoires and Practices, carried out by the Contrapunto team, is based on the study of ‘other’ sources, environments and kinds of music that are little used in general music historiography. Now, I would like to present some of these. We have consulted, for instance, the writings of the humanist, philosopher and educator Juan Luis Vives (1492-1540); works of the philosopher and poet Giordano Bruno (1548-1600); or the musical theorist Fernand Estevan (fl. 1410). Our aim was to reflect on the concept of a musical work and to carry out an ontological investigation concerning Renaissance musical works that tell us about the past, but also project us towards the future through their potential for (re-) materialization as sounding music.

We also consulted such peculiar literary texts as those of the aristocrat, soldier and poet, Íñigo López de Mendoza, the first Marquis of Santillana (1398-1458), or the Arte de trovar (ca. 1427-33) by the astrologer and writer Enrique de Villena. The purpose here was to rethink the uses of interpretative practices in 15th-century songs with Castilian texts and the limits of these practices in relation to their potential classification as musical works.

We further looked at the incunable dictionaries of Antonio de Nebrija (1441/44-1522), Alfonso de Palencia (1423-1492), and the interesting but almost unknown anonymous treatise, the Arte de la melodía sobre canto lano y canto dorgano (ca. 1475-1525 [Barcelona, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Ms. 1325/2, ff. 21v-24r]), among other sources, in order to study the gloss and its limits as an identifying element of musical work

The results of our research have been set out in the volume Making Musical Works in Renaissance Spain, of which John Griffiths and I are the editors and which will come out shortly (Turnhout: Brepols). So as not to bore you with too much information, I would just like to say that this volume also includes case studies focused on concrete pieces of which a considerable number of copies have been preserved. For example, the romance Los brazos traygo cansados has been dealt with as an example of constant updating; while the hymn Pange lingua set by Juan de Urrede possesses a symbolism that shapes it into a work.

There are also other contributions that we believe will be of interest to the reader, such as the one dedicated to identifying the musical works contained in the immense library of Hernando Colón (1488-1539) – a son of the well-known explorer, Christopher Columbus - on the banks of the River Guadalquivir, in Seville, with exactly 15.344 volumes, until now only partially examined.

We hope to be able to continue our research in a future project, where one of the central foci will be the study of the Palace of Peñaranda de Duero, an exceptional research object previously unstudied by musicologists, and one which I would like to talk about more in my next post.

Series of four posts by Soterraña Aguirre Rincón: Blog post I

Do we need the concept of the ‘musical work’ to make a music history? This is a simple question to which it is not easy to offer an answer. If we answer it restrictively, we would have to say that its use is only relevant for the study of the music of the 19th century and much of the 20th century. But it is also quite possible that we might accept its validity for music from the 15th century onwards. As John Butt pointed out, ‘within the context of the European tradition, there is for many … an essential transhistorical unity implied by the concept of a work’.[1]

CC BY Soterraña Aguirre Rincón NC SA

CC BY Soterraña Aguirre Rincón NC SA

The ‘musical work’ has been the subject of vibrant and productive discussions since the late 1960s,[2] but the debate has become more widespread since the 1990s, when English-language musicology began to concern itself with the subject. We all remember in this respect the impact of Lydia Goehr's controversial and emblematic book The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992).

Goehr’s study dealt with the historical period (the end of the 18th century) in which a specific way of conceiving the musical work (which in the book appears as the only one) became the regulating force of the musical practices of the following centuries. Goehr highlighted the relevance of the notion of Werktreue in the fields of music and theatre. She also underlined the powerful influence that the work concept had in legitimizing certain musical practices over others. Her book without doubt revealed a fissure in the dominant ways of thinking and made room for new arguments and ideas. In my opinion, this was one of its main contributions.

Goehr’s most direct impact came from her claim that the element of time – of history - was a necessary component for understanding the meanings of the term ‘musical work’. Goehr marked the turning point as ca. 1800, the period when – according to her - composers began to conceive of their craft not just as music, but as ‘works’. Hence, we can’t properly speak about the ‘musical work’ before that moment as an aesthetic and regulative concept. This argument has been criticized for creating a certain historical discontinuity and, consequently, for excluding creations such as those by Bach or Mozart from the terrain of the ‘work’.

Theorists such as Polish philosopher Władysław Tatarkiewicz and British critic Terry Eagleton previously concluded that the concept of the ‘work of art’ had been established during the second half of the 18th century, intertwined with other ideas about art, autonomy, creativity (or genius), beauty, form and aesthetic experience.[3] However, as the Spanish researcher Pilar Ramos points out, ‘Tatarkiewicz was not interested in addressing issues such as the origins, continuity or discontinuity of ideas throughout history, but chose to focus on the various meanings given in each historical period to terms such as creator, work, art, mimesis, etc.’.[4]

In an attempt to clarify this ‘problem’ within the musicological field, and to try to allow space for the ‘idea’ and the ‘process’ of the musical work, in 1998 the symposium The musical work: reality or invention? was organized at the University of Liverpool.[5] On this occasion, speakers belonging to several research fields, such as musicology, ethnomusicology, anthropology or philosophy, shed light on this theme from very different perspectives. All the participants tried to reach an agreement on what a ‘musical work’ is, whether from a timeless perspective or in a concrete historical situation, and some consensus was reached in defining a musical work as ‘discrete, reproducible and attributable’.[6] This is an inclusive conception of a musical work, but it is also somewhat imprecise and therefore difficult to use.

There is no doubt, however, that the concept of a musical work was already used in the 15th century.[7] Several researchers have analyzed this concept. Almost inevitably, they examine it as a progression towards the idea of a musical work of art in the sense understood in the 19th century, differentiating the 19th-century concept from how they believe the concept of a musical work was used and materialized in the fifteenth.

My research team Contrapunto has sought to understand Renaissance music from the perspectives of both observation and analysis. To this end, we designed the project The Renaissance Musical Work: Fundamentals, Repertoires and Practices which I lead.[8]

Our interest in examining ‘other’ sources, environments and musics that are little used in general music historiography, together with the plurality of methodological frameworks that we use to achieve our objectives, are premises that our project shares with MALMECC. Hence our interest in collaborating and sharing results and experiences.

Soterraña Aguirre Rincón

Profesora Titular in Musicology

University of Valladolid (Spain)

[1] John Butt, ‘What is a ‘musical work’? Reflections on the origins of the “work concept” in western art music’, in Concepts of Music and Copyright: How Music Perceives Itself and How Copyright Perceives Music, ed. by Andreas Rahmatian (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015), 1-22, at 2.

[2] See for example, Carl Dahlhaus, ‘Plädoyer für eine romantische Kategorie: Der Begriff des Kunstwerkes in der neuesten Musik’, Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 130 (1969), 18-22, or Zofia Lissa, ‘Über das Wesen des Musikwerkes’, Die Musikforschung, 21/2 (1968), 157-82.

[3] Władysław Tatarkiewicz, A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1980). Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990).

[4] Pilar Ramos, ‘Defraudar la compostura: On Musical Glosses, Musical Works and Authors’, in Making Musical Works in Renaissance Spain, ed. by Soterraña Aguirre Rincón and John Griffiths (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming).

[5] Organized by James Michael Talbot and Constance Alsop. Its results were published as The Musical Work: Reality or Invention?, ed. by Michael Talbot (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000).

[6] See also Giuseppe Fiorentino, “The Concept of Musical Work in the Spanish Renaissance: A Lexical Inquiry” in Making Musical Works in Renaissance Spain (forthcoming).

[7] See, for example, Laurenz Lütteken and James Steichen, ‘The Work Concept’, in The Cambridge History of Fifteenth-Century Music, ed. by Anna Maria Busse Berger and Jesse Rodin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 55-68.

[8] Financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness [HAR2015-70181-P].

Interview with Grantley McDonald, Post-doc researcher on the MALMECC project

What attracted you to this project?

I have been working on a large-scale project on the court chapel of Maximilian I Habsburg (1459–1519) since 2016. At every turn I became aware how much its structures, practices and personnel drew on the chapels of his immediate predecessors: his father, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III, Archduke Sigmund of the Tyrol, and Duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy. I was attracted to this project by the chance to explore more fully the musical life of these earlier courts, in an environment that would lead me to look at the materials in ways I had not previously considered, and with some colleagues whom I admire tremendously.

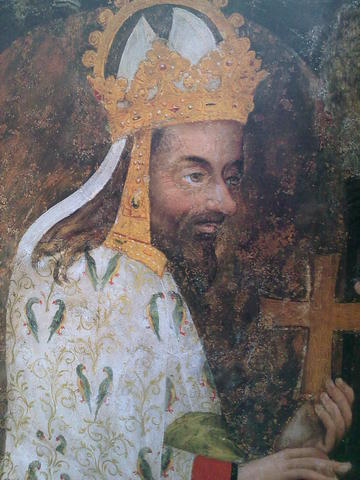

The court chapel of Maximilian’s father Frederick III in particular is desperately under-studied, despite Frederick’s central position in the politics of Central Europe during the fifteenth century. Most nineteenth-century historians dismissed him as ineffectual and cranky, but the diligent work of some recent German and Austrian historians, and the systematic examination of the written records of his reign, have begun to reveal his true importance. This revision of Frederick’s historical and political importance really demands a reassessment of his musical legacy.

Why do you think this project is important or original?

I have long been fascinated by Isaac Newton. Besides his pioneering contributions to the natural sciences and mathematics, Newton was obsessed by historical, theological and prophetic questions, as his voluminous papers attest. Things are different now. As disciplines become ever more specialised, they develop their own way of examining, testing, and talking about their object of study. Ideas and hypotheses are evaluated; ever more workable ideas and techniques are developed, and inaccurate or untenable notions are winnowed out. This is true not only in the natural sciences, but also in the humanities, where the objects of study are “softer” and more difficult to pin down. Nevertheless, while the creation of such subject-specific discourses permits individual fields to move forward, it also means that it is difficult, if not impossible, for an individual to master the discourse – and the attendant literature – of several different academic specialisations. If he were alive now, even Newton would have found it a challenge to operate at the cutting edge of both theoretical physics and biblical criticism. However, working in a team made up of individuals with different specialisations is one way of profiting simultaneously from the approaches and advances of multiple fields, and of stimulating fruitful new lines of enquiry.

MALMECC has the added challenge of operating within the field of mediaeval studies, which has long served as a crucible of nationalistic and religious agendas. Responding to recent developments in the “new mediaeval studies”, we are trying to disrupt the agendas of earlier generations of mediaevalists by asking different questions of the material and questioning the narratives underlying earlier work.

My own part in the project combines these stimulating new intellectual challenges with what is perhaps a very traditional way of working: by trawling the archives of Europe to gather vast quantities of previously unpublished material recording the lives and activities of the members of the chapels of Frederick and Maximilian, to create what historians call a “prosopography”, a collection of life data on a circumscribed group. After a while, historical work on a given period or situation can start to turn in circles once scholars have digested and discussed the available source materials. The publication of new source materials provides the necessary fuel for new discussions, but it’s hard going. Working in archives is like looking for pieces of a jigsaw in an exploded building. It can be wretched, boring, and unexpectedly draining. Once a document has been located, it must be transcribed and analysed, and these tasks require advanced skills in palaeography and various dead languages, as well as knowledge of the historical background and interpretive acumen. But once you start to build up a body of documentary evidence, all the little bits of the jigsaw start to fall into place. You’ll probably never find all the pieces, and you will have to chuck out bits that belong to other puzzles, but once a picture starts to emerge, it’s electrifying. That shiver of uncovering past lives sends you back into the archive the next day. And the next. And the next. More importantly, the location, transcription and publication of previously unknown materials is an indispensable part of keeping historical discussion fresh and dynamic.

Which aspects of courtly culture in mediaeval times do you find most interesting and why?

In the present project, I have become fascinated by the intersections between the structures of the court and the structures of the church. The Holy Roman Emperor had a mission to promote the interests of the church. In the fifteenth century, this meant fighting against Hussitism and the advance of the Turks; in the sixteenth, it still meant fighting back the Turks, but also involved stopping and – if possible – reversing the gains of Protestantism. So the relation between the church and the imperial court is particularly interesting. As elected head of a confederation of nobles, the Emperor also had to project the power of his personality and authority. One of the things I am investigating is the way music was used to do that – in a sense, how music was instrumentalised as a political and even as a propagandistic tool.

What message would you like to communicate through your work on the project?

One of the explicit aims of MALMECC is to challenge the nationalistic narratives that have in the past run though mediaeval studies, and to an extent still do. The history of the Holy Roman Empire has almost always been written as a German and Austrian story. On the other hand, while the five-hundredth anniversary of Maximilian’s death in 2019 prompted numerous conferences and major exhibitions in Austria and Germany, the event was marked by no comparable events in Belgium or the Netherlands, even though Maximilian, as Duke of Burgundy, ruled the Low Countries for some fifteen years. I wanted to shake up such silly parochialism. Besides working in major archives in places such as Vienna, Innsbruck, Weimar, Augsburg, Nuremberg and Karlsruhe, I have also looked further afield, to central archives in places such as Rome, Milan, Ljubljana, Prague, Strasbourg, Brussels, Lille, the Hague, Ghent, and Bruges, as well as to numerous small town and church archives throughout Europe. This has revealed that the activity of the Holy Roman Empire involved much more than simply Germany and Austria, but sent out tentacles across the continent.

Secondly, I want to reveal something of the lives of the members of the chapels of Frederick and Maximilian. Partly because the source situation is so difficult, we have in the past found it hard to understand most musicians of the Middle Ages as people, with a few exceptions, such as Guillaume de Machaut. But by collecting vast amounts of information about individual musicians, I have come to know many of them as interesting individuals: emotionally fragile organists, undisciplined and unruly singers, priests hustling for promotion within the Church hierarchy or providing for their illegitimate children, trumpeters negotiating a pay-rise or a pension for their wives. And all this fine-grained texture about the lives of members of the chapel and other musicians can bring their music to life in surprising ways.

What got you interested in mediaeval music and what do you like about it?

As a kid I sang in the choir of St Paul’s cathedral in Melbourne, and at our parish church. Even as a child I was drawn to mediaeval and Renaissance music, and devoured recordings by David Munrow, the Tallis Scholars and Gothic Voices. As an over-eager high school student I wrote a long essay about the Roman de Fauvel, complete with a recording which I had made with some friends, huddled around a tape recorder. As an undergraduate in Melbourne I was fortunate to work with some very erudite conductors, such as John O’Donnell and John Stinson; under John Stinson I sang in a group called Les Six, which specialised in fourteenth-century Italian music. I also continued my vocal studies with Vivien Hamilton and Stephen Grant, who sang with the mediaeval ensemble Sequentia. After moving to Europe I started to sing with other early music ensembles, such as Diabolus in Musica (Tours) and Cappella Pratensis (Den Bosch/ Leuven). I find the combination of elegance, intellectualism, and raw energy in this music immensely appealing.

What reactions do you get from new audiences, such as children?

During a US tour with Cappella Pratensis last year, we had the chance to work with groups of high-school students and undergrads, such as a group of the students of the wonderful Jenny Bloxam at Williams College in Massachusetts. With the high-school kids, we worked on things such as tone and articulation as ways to express the text. Cappella Pratensis specialises in performing from facsimiles of original sources, and after a few hours we had Jenny’s students doing likewise. Their delight at being able to sing from notation which at first seemed foreign was palpable. After a concert in New York, a young poet even sent us a package of delightful Neo-Spencerian poems in praise of the ensemble and the performance. We hope that the kind of research we are doing in MALMECC will resonate both with our own peers and with students of the next generation who come to study mediaeval and Renaissance music more deeply through their own experiences as performers or listeners.

Our understanding of medieval culture vastly relies on fragmentary sources. Musicologists are especially well-acquainted with this — most historians working on pre-1500 music rely to a significant extent on ‘waste’ parchment as a source of information about lost musical cultures. Working with fragments is challenging; however, it can also yield extremely rewarding results when we are able to reconstruct a wider picture.

In a recent publication, I re-examined a group of musical fragments preserved in Catalan archives. They transmit a highly sophisticated repertory inspired by the musical practices of late fourteenth-century cardinals and popes in Avignon, alongside northern French aristocratic and royal households. My essay traces the provenance of these fragments, recalibrating the way we think about the connection between the original manuscripts, local ecclesiastic and courtly institutions, and individual clerics. To make a long story short, most of the manuscripts converge with the itineraries of King John I of Aragon (b. 1350, r. 1387-1396) —who was an enthusiastic lover of music— and his court. The rather concrete picture emerging from my study confirms the long-held hypothesis that the royal court of Aragon was a major force behind the dissemination of this refined musical repertory throughout late medieval Catalonia.

In order to make the results of my research accessible to non-specialists, I have put together a ten-minute video. I couldn’t resist including footage of some of my favourite medieval towns and buildings. I hope you’ll enjoy watching it.

David Catalunya

Life Imitating Art Imitating Life Imitating Art Imitating Life? A Peek at Machaut and Le Franc – Part IV

Uri Smilansky

Last part, I promise!

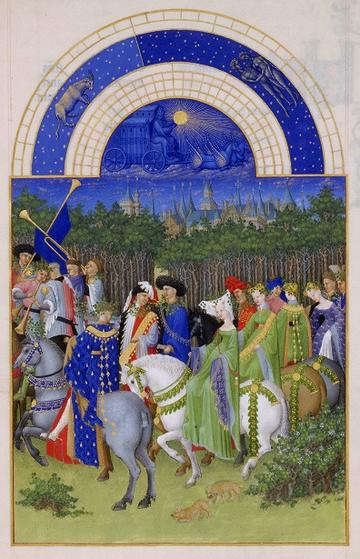

So, there you have it. We’ve encountered Guillaume de Machaut’s literary influence on Martin Le Franc, and suggested the earlier poet’s name still resonated at the Burgundian court in the middle of the fifteenth century. We’ve mirrored art and life, juxtaposing Machaut’s Boethian Remede with Le Franc’s framing of two literary works and two books within the intellectual politics of the court of Burgundy. We’ve seen how this mirroring might have been achieved, and what Le Franc could have gained from it. Now, the question is how any of this can affects the way we view courtly culture.

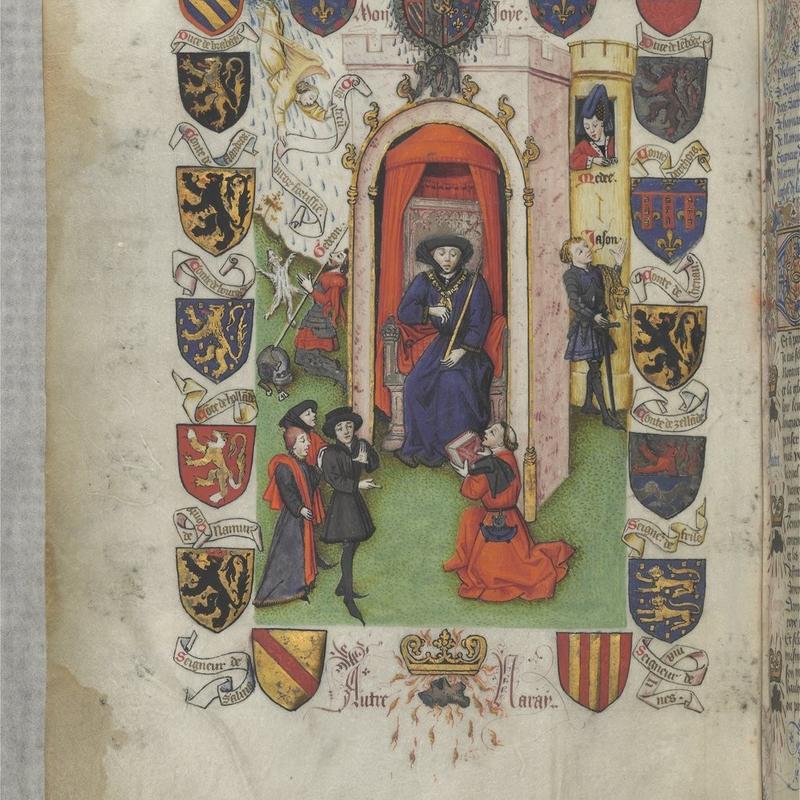

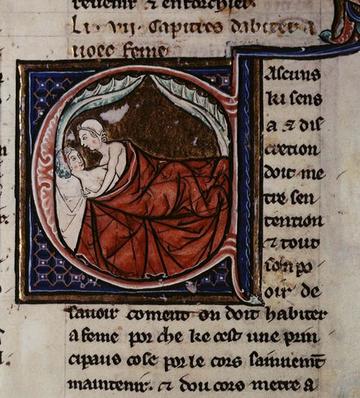

I ended the previous instalment suggesting that the story told by the manuscript Paris, BnF fr. 12476 is subtly yet materially different from its actual, textual and visual content. Regardless of what one thinks of this specific case, allowing such readings forces a deeper interaction of material culture and situational context into literary, artistic and musical analysis. Texts accrue meanings beyond their words, not only through their presentation, ordering and juxtaposition within each manuscript source (Huot, 1987), but also with each interaction of users with the book as object. Clearly, not all interactions are as carefully managed as that orchestrated by Le Franc for the presentation of this manuscript. Nevertheless, crafted intentionality can be read into any book-presentation or gift-giving ritual, and even into book-loaning at court. This, of course, relates also to the literary use of books, especially when this involved an intentionally communal consumption, with discussions appending readings (Kelly, 2017).

The notion of communal interpretation of cross-literary-courtly behaviour that underpins these blogs links to many other established directions of research. The social performance component clearly relates to discussions of the orality of literature (Coleman, 1996; McGrady, 2006). It ties in with institutional research into the operation and use of princely libraries (Wijsman, 2013). I have already highlighted its relevance to interpretations of the use of allusion within courtly life (Plumley 2013), and the whole affair underlines performance—of literature, or of courtly, social ritual—as an integral component of creating meaning. This is taken for granted within the realm of linguistics, taking it to be a building block of communication. Musicological, art-historical and literary analyses, however, often shy away from incorporating performance within their models of meaning, no doubt due to our distance from both original performers and audiences, and the meagre evidence we have concerning their techniques and aesthetics.

Finally, I’d like to throw some questions out there, which go clearly beyond the current context and medium. These relate to more general notions of time, contemporaneity, memory and relevance. How was the border between contemporaneity and the past navigated? Were works by Machaut thought of as current a century after their composition, or did they act as relics of an authoritative past? Did Machaut have special status in this regard? How did his oeuvre compare to the scores of other writings circulating and being reproduced long after the demise of their authors, for example, the thirteenth-century Roman de la Rose? Could audiences easily date the works they were consuming? Did dating matter beyond the notion, that something was ‘old’? To what degree do such considerations rely on the objects in which works are contained? Is an old work in a new book new or old? In what other ways did owners and courtiers engaged with new books? Were old books cherished for their literary contents, or as tokens of dynastic inheritance? Were they used, or simply preserved? Assuming at least a few of Machaut’s works did remain in some publics’ imagination for a century or so, how did this manifest itself? Were they remembered in detail? Were they viewed as idealized tropes? Or viewed not at all, with only his name acting as a nebulous tag of authority?

With so many questions still outstanding at the end of the analysis, at least intellectually, none of us will be out of work any time soon. I hope this has encouraged some of you to carry on thinking along these lines. If that happens, these multiple entries will have been well worth the effort.

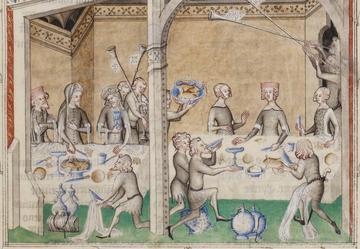

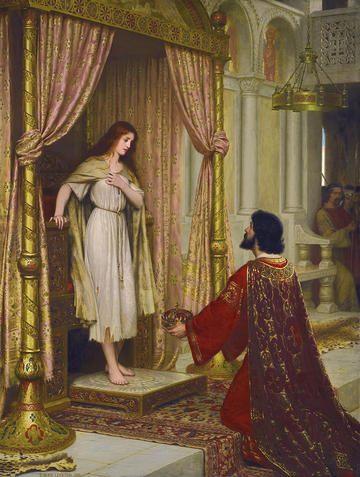

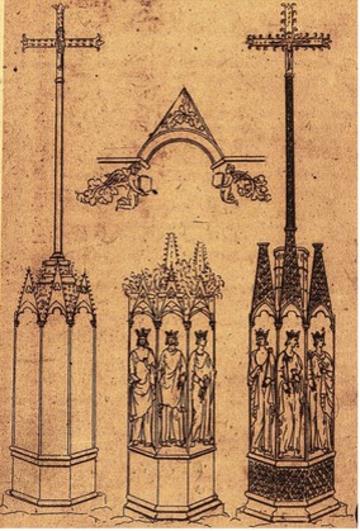

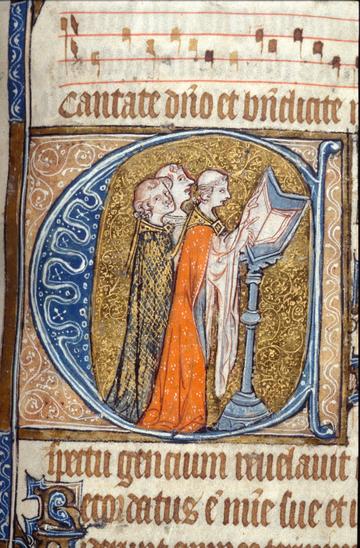

Image: French gift book detail

Selected further reading:

Sylvia Huot, From Song to Book: The Poetics of Writing in Old French Lyric and Lyrical Narrative Poetry (Cornell University Press, 1987).

Douglas Kelly, ‘Judgment at Court: Open Thought and Prudent Dissimulation in the Anonymous Livre du Tresor amoureux’, in R. Barton Palmer and Burt Kimmelman (eds), Machaut’s Legacy: The Judgment Poetry Tradition in the Later Middle Ages and Beyond (University Press of Florida, 2017), pp. 9-27.

Joyce Coleman, Public Reading and the Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Deborah McGrady, Controlling Readers: Guillaume de Machaut and his Late Medieval Audience (University of Toronto Press, 2006).

Hanno Wijsman, ‘Book Collections and their Use: The Example of the Library of the Dukes of Burgundy’, Queeste, Journal of Medieval Literature in the Low Countries 20 (2013), pp. 83-98.

Life Imitating Art Imitating Life Imitating Art Imitating Life? A Peek at Machaut and Le Franc – Part III

Uri Smilansky

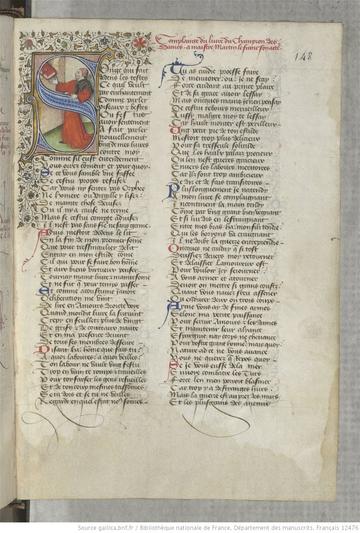

In the first two postings of this series, I’ve presented a couple of works by Martin Le Franc, a couple of manuscripts in which they were first copied, and traced their accepted or potential relationships to some of Guillaume de Machaut’s oeuvre. In the second post, I suggested one can choose to see a purposeful remodelling of Machaut’s Remede de Fortune narrative structure in Le Franc’s decision to compose the Complainte du Livre du Champion des Dames and present his Champion des Dames for a second time at the same court. According to this reading, both court and author—along with his two poems and two books—become characters in a meta-fictional performance of courtliness and cultural consumption. This raises many questions, though I will only mention three here. Why would Le Franc choose to act in this manner? Would this remodelling become apparent to his contemporary audiences? How was it enacted?

We cannot tell exactly why Le Franc decided to present his Champion des Dames to the same patron twice, a decade apart. Whatever the actual reasons, I believe this procedure was unusual enough to lead him to take precautionary action before undertaking it. After all, if the work was indeed rejected when new, would a new presentation not imply that the Duke of Burgundy and his court were wrong in their original judgement? If it was accepted back then (either enthusiastically or indifferently), why would the author presume his patron required a new version? True, princely libraries often contained multiple copies of single works, but these were usually the result of inheritance or commission, not of authorial presentation. To my mind, a second presentation would have required careful management on Le Franc’s part. It needed to be done in such a way as to explain the repetition of the act of presentation of the book by Le Franc to Philip the Good, and—assuming he was hoping for a more positive reception at his second attempt—provide both patron and court with an avenue through which they could change their reaction to the work without losing face. This is where Machaut’s model comes into play: the use of an established literary trope recast to retrospectively explain real-life events would have offered exactly such a narrative paradigm. The Remede model presents a successful reintegration into court. At the point of the Champion’s second presentation, this could not have been guaranteed, as the second book (now Paris, BnF fr. 12476) had not yet been accepted by Philip and his court. Le Franc’s use of the Remede as model, however, creates the expectation of a positive resolution, and provides both court and its patron with a moral justification to change their minds: it was the original presentation that was faulty, not their judgement upon it, or, indeed, the work itself.

This is all very well, but such modelling would only be effective if it was recognized by the books’ recipients. Previously, I suggested that at least in the particular case of the reception of Machaut’s oeuvre in mid fifteenth-century Burgundy, adaptations, citations, references or allusions to materials a century or more old were intended to resonate with contemporary audiences rather than function as unacknowledged tags of an author’s learnedness for the benefit of future specialist readers. Indeed, it seems reasonable to suggest that such techniques, when used in works designed for presentation to a courtly audience, always relied on at least some listeners picking up on their significance (Plumley, 2013). Otherwise, they make little sense. If this was indeed the case, what would stand in the way of this audience familiarity underpinning the performance of similar relationships between old and new within managed courtly rituals such as book presentations? If meta-fictions and pseudo-realities were so eagerly consumed within late-medieval literature, why not act out meta-realities and pseudo-fictions within courtly life?

This leaves the question of technique. How would the relationship to Machaut’s Remede be communicated? One issue is that of specificity. For Le Franc’s fictionalized description of events to work, it would have been enough for the courtly audience to recognize a more general ‘consolation’ trope where adversity is successfully overcome. An association with the Remede—with its specifically courtly setting and near obsessive presentations, descriptions and discussions of performance—would have been ideal for Le Franc’s needs. Nonetheless, vague echoes of Boethius’ De consolatione philosophiae (c. 524) in its Latin original or in any one of its many French translations and reworkings would probably have sufficed for his pretence to have worked (Cropp, 2012). This reduces the pressure to associate the proceedings with Machaut specifically and allow access also to consumers without this degree of prior knowledge.

Either way, the viability of any external allusion relies on the recipients noticing that Martin Le Franc added the new Complainte at the end of the Paris manuscript. To recap, this is the only work in that book beside the Champion, they are linked though scribal hand and illuminator, and there is no sign of separate origins for the two works. This joining seems original, and as the main textual difference between the Paris and Brussels books, it would have been easy to point towards the addition during a presentation ritual. The joint binding of the two works acts as a continuous reminder of the artifice they are engaged with, thus imbuing them with additional interest beyond their actual content. Furthermore, the relationship between the two works is readily apparent just from reading their rubricated titles. Combine this with the physical object of the presentation book that contains them and with a familiarity with the Consolatio / Remede narrative model, and it becomes possible for the books’ owners mentally to reconstruct or remember Le Franc’s meta-narrative without even hearing his poetry. The book’s physical location and intellectual context tells a story that, while authored by Le Franc, is not contained within it. One can go as far as suggest that while his work may well have been better received upon its second presentation, the very artifice used to enable the occasion may have caused a reduced likelihood for textual engagement with its contents. Courtly artifice—represented through the meta-fictional exchange outlined here and the dissonance between literary content and the new illumination programme of the Paris copy—may have won over contents.

In the next instalment, I ask: “So, what?”

Selected further reading:

Yolanda Plumley, The Art of Grafted Song: Citation and Allusion in the Age of Machaut (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Glynnis M. Cropp, ‘Boethius in Medieval France: Translations of the De consolatione philosophiae and Literary Influence’, in Noel Harold Kaylor, Jr. and Philip Edward Phillips (eds), A Companion to Boethius in the Middle Ages (Brill, 2012), pp. 319-55.

Transl. by David R. Slavitt (trans.), Boethius: The Consolation of Philosophy (Harvard University Press, 2010).

A Peek at Machaut and Le Franc – Part II

Uri Smilansky

Previously on the MALMECC blog: in the last post, I traced a few links between Guillaume de Machaut and Martin Le Franc and left some questions hanging as to how far they can be stretched. This is the focus of today’s instalment. My suggestion first involves a widening of the range of works to be compared, and then allowing the comparison to take a step beyond the world of literature. The work I have in mind is Machaut’s Remede de Fortune (early 1340s?). The comparison with Le Franc is not directly with any of his literary works, but with his retrospective fictionalization of the events surrounding the double presentation of his Champion, and the composition of the Complainte described in Part I. Instead of a literary space, Le Franc uses the Burgundian court to portray a real-life version of Machaut’s fictional model of courtly rejection, reinvention and eventual acceptance, with himself, his books and his literary creations acting as characters in the story. See what you think.

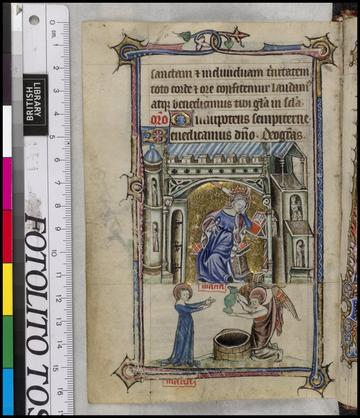

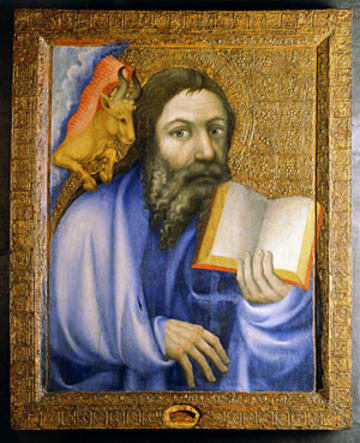

NY Morgan library and Museum MS M 396 fol 67v detail

The Remede is not an overtly biographical work, though its compositionally-minded and active first-person narrator invites a certain amount of conflation between character and at least an idealised author-figure. As a result, this work has been taken to attest to a number of extra-literary processes. These include the formation of, at a minimum, a professional relationship between Machaut and Bonne of Luxembourg (May, 20th, 1315-September, 11th, 1349), the supposed dedicatee of the work, conflating her with the character of the beloved (Wimsatt and Kibler, 1988); Machaut’s didactic relationship with the future Charles V as a child (Leo, 2013); and the literary reframing of a real-world, contemporaneous transition from old to new musical and poetic possibilities and conventions (Switten, 1989, Brownlee, 1991).

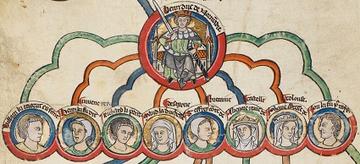

The narrative arc of the Remede is presented in a much-simplified version in the first column of the table below. Central events and structural points of change are highlighted within the narrative through lyric interpolation, with seven of the nine insertions sporting musical settings in the majority of surviving versions (and, notably, in the central group of sources close to Machaut’s person). These self-contained pieces work as a set, offering a single instance of each courtly genre of the day, and presented as moving simultaneously towards poetic simplification and musical innovation. The middle column of the table details their locations within the narratives, as well as giving some more detail of the events of the Remede. Finally, I have added a third column to the table, where the parallels between Machaut’s and Le Franc’s creations are mapped out. Beyond the transition from a literary space to that of the Burgundian court, this requires the substitution of Machaut’s literary protagonist, the amant, with Le Franc’s literary work, the Champion. Placing a literary creation as a character is, of course, problematic. Le Franc overcomes the problem of this (relative) fixity in two ingenious ways. First, the ventriloquizing of the Champion’s first presentation copy—now Brussels, KBR, MS 9466—within the Complainte permits it to acquire a narrative presence within the fictionalized proceedings. Second, the creation of a new, physically distinct version of the same text—now Paris, BnF fr. 12476—, visually differentiated through the integration of a new illumination programme and the Complainte, allows for the material performance of change without the text changing or losing its identity.

Part I of IV

Uri Smilansky

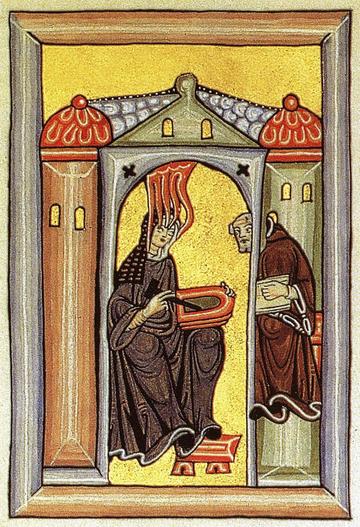

Helen Swift has written extensively (2017, but also 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2013) about an extraordinary work, the Complainte du livre du Champion des Dames a maistre Martin le Franc son acteur. Martin le Franc (c. 1410-1461) must have composed this 60-strophe dream-poem by 1451, this being the date of its first surviving copy. As the name suggests, the poem dramatizes a debate (or rather, mud-slinging match) between a book containing Le Franc’s major work—the 24,000-verse and much better-known Champion des Dames (c. 1442)—and its author, following its supposedly unsuccessful presentation at the Burgundian court. It will surprise no-one to hear that, following a learned Boethian discussion, the author clears himself of any wrongdoing.

As luck would have it, this very same talking book—or, in any case, the one presented to the Duke of Burgundy and that the Complainte purports to ventriloquize—has survived to this day as Brussels, KBR, MS 9466. Even more fortuitously, the earliest surviving version of the Complainte mentioned above is appended to a second copy of the Champion, also presented at the Burgundian court only a few years after that of the Brussels manuscript (a colophon on fol. 147v attests that the Champion’s text was copied in, though this is by no means the end of the creation process). This second book is now Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, français 12476

The addition of the Complainte to the second, later copy of the Champion suggests that lessons have been learned from the first attempt, a notion further strengthened by the enhanced presentation of the second volume. While its main text remains virtually identical, it offers 66 illuminations compared to the first version’s two, with Pascale Charron (2000) demonstrating that the new visual programme was geared specifically to appeal to Burgundian viewers. They highlight the anecdotal, narrative elements of the Champion des Dames rather than its extensive polemical and moralizing elements, the latter being some of the accusations levelled by the book at its author as having caused its negative reception. Regardless of whether the first book was indeed poorly received (which is by no means certain), the presentation of a new copy with the shorter poem at its end creates a performance in the real world which validates its own artistic content by imitating the actual, imagined or invented real-life events surrounding its predecessor.

So far, so good, but what does this have to do with Machaut? Well, Le Franc mentions Machaut (c. 1300-1377) three times in the Champion, demonstrating not only his own knowledge, but an expectation of familiarity among his audiences.

The mid-century Burgundian book-collection, after all, contained a number of Machaut manuscripts (now sadly lost), and the venerable author of three generations earlier knew and dedicated works to the founder of the Valois-Burgundian dynasty, Philip the Bold (1342-1404), this being the grandfather and namesake of the Duke to whom Le Franc presented his works, Philip the Good (1396-1467). Furthermore, Machaut has been credited with important contributions to many of the literary topoi found in Le Franc’s work, from the structural use of debate, to concepts theorized in modern criticism as intertextual, metatextual, transtextual and metafictional. Perhaps the most visible parallels between the outputs of the two authors are the centricity of performance and its discussion as the driving forces behind central plotlines, and the use of false retraction, whereby the relationship between Le Franc’s Complainte and Champion mirror that between Machaut’s two judgement poems, the Jugement dou Roi de Behaigne (before 1346; mid-1330s?) and the Jugement dou Roi de Navarre (c. 1349). Suggesting a nod towards the earlier master is thus not overly controversial.

Comparisons between the two authors are usually, and understandably, confined to comparing their respective literary outputs, and most often relate to Machaut’s debate poetry. Still, Le Franc’s explicit conflation between art, life, book and performance—echoing and expanding upon Machaut’s earlier tendencies—perhaps gives license to casting the net wider. But how much wider? And what would the net ensnare? Tune in to the next instalment in a couple of weeks, or send your own suggestions on a 21st Century postcard, via Twitter.

Selected further reading:

Gaston Paris, ‘Un poème inédit de Martin Le Franc’, Romania, 16 (1887), pp. 383-437.

Helen J. Swift, ‘Courting Controversy? Poetic Manipulation of Politics in the Mid-Fifteenth Century’, in R. Barton Palmer and Burt Kimmelman (eds), Machaut’s Legacy: The Judgment Poetry Tradition in the Later Middle Ages and Beyond (University Press of Florida, 2017), pp. 62-86.

Pascale Charron, ‘Les Réceptions du Champion des dames de Martin Le Franc à la cour de Bourgogne: ‘Tres puissant et tres humain prince [...] veuillez cest livre humainement recepvoir’’, Bulletin du bibliophile, 1 (2000), pp. 9–31.

R. Barton Palmer, ‘The Metafictional Machaut: Reflexivity in the Judgment Poems’, in R. Barton Palmer (ed.), Chaucer’s French Contemporaries: The Poetry/Poetics of Self and Tradition (New York: AMS Press, 1999), pp. 71–92.

R. Barton Palmer with Domenic Leo and Uri Smilansky, The Debate Poems, in R. Barton Palmer and Yolanda Plumley (eds), Guillaume de Machaut: The Complete Poetry & Music, volume I (TEAMS, Medieval Institute Publications: Michigan, 2017).

An interview with Dr. Uri Smilansky January 2020 by Project Coordinator, Claire Selby.

Today we welcome Uri Smilansky who is going to talk about his role in the MALMECC project.

What attracted you to this project?

“I believe that in order to understand a cultural system, we have to look at it in the round. While it is entirely understandable that people latch onto the little bit (of culture) that they enjoy most or specialise in studying, at some point there comes a time when, if we don’t look outside our ‘own box’, we are very likely not only to miss out on what’s going on around us, but not even to be able to understand its appeal fully - so I was very pleased to be able to join a project that shared this viewpoint.”

Excellent to hear! What do you think is original about the project’s approach to medieval European culture and what kind of original thoughts can we extract from it at the end?

“I think MALMECC goes beyond most projects in terms of the degree of cooperation between various research techniques and interests. While it has music in the title, it is less geared towards a specific view of music’s place in the world or having to channel everything through discussions of music. The broader disciplinary scope of the project means it is more able to bring together what are really independent, wide-ranging interdisciplinary examinations.”

Uri, I know that you have your own specialism within the project, so I thought it might be interesting to hear which aspects of courtly culture in medieval times you find most interesting and why that might be.

“Well, I have been working on French music for more years than I care to remember by this point – music throughout the 14th and 15th centuries - so I was naturally attracted to that aspect of the project. A while ago, I also worked on a project collating a new edition of the works of Guillaume de Machaut, which involved transcribing, translating and looking at manuscripts with very close attention to the words and notes, which on the one hand was fascinating and I enjoyed it very much, but on the other hand raised a lot of questions that I was able to follow up on at the time. Questions such as: What would you do with these notes afterwards? How would they be understood? Would they be listened to? Are they (the scripts and scores) just objects to look at rather than to listen to? How widely were these materials distributed? How did they sit alongside other non-musical aspects of culture in the wider social context? That’s where this project comes in. It allows me to look at similar material, but from an entirely different starting point. I hope I can bring my previous knowledge of manuscripts and experience of analysing cultural materials to the process of re-examination in a wider context now.”

What would you like to achieve through the work of this project?

Within the project, my main goal is perhaps best described as disciplinary. In conversation with musicologists, I’d like to encourage the trend away from ‘pure’ musical interests and musical abstractions. Instead, I try to show how deep the need is to examine musical materials also when they are not being used for music making, as material presence, as well as to improve our models of engaging with music’s mediation through performance. When working with non-musicologists – researchers in literature, poetry, art history and architecture – I want to encourage them to connect with the idea of performance of sounds and music, even without having specialist training in music. Researchers perceive a lack of training in music as a barrier and it is often the case that when you mention medieval music, they say, “Oh, I don’t know anything about that. Let’s look at something else!” so I’d like to help break down those barriers.

It has always been the case that music is not just for specialists. I’d like to work on expanding the understanding of music as a social topic within the context of other aspects of culture. Analysing music by itself makes little sense and one should try to understand everything from architecture to fashion in order to be able to find a starting point for analysing the notes. If we start by analysing the notes on the page and only then move to thinking about who listened to them and what their preconceived notions and mental attitudes towards listening were, there is a risk that we base our initial analysis on our own knowledge and attitudes, rather than trying to understand what the music meant to its listeners at the time. That’s why a project that considers music in its wider context is very important to me.

The trick, of course, is to try and talk to both audiences at the same time.”

That is fascinating! We look forward very much to hearing more and learning about its conclusions as the project progresses. Thank you very much for your time today. We are grateful to Uri Smilansky of the MALMECC project for those thought-provoking insights.

Blogs 05 2019 - 11 2019

Uri Smilansky

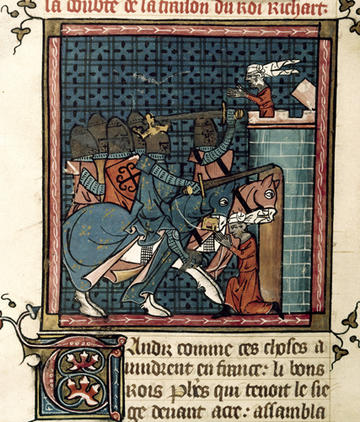

First days are always stressful, especially when your new colleagues seem to know everyone already, and are willing and ready to fulfil any request made of them. Such days are even more intimidating if one arrives four years into a project to be presented with a smooth-running operation which has established its own protocols and habits. But enough about me. This is not about the new team members at MALMECC: we have been warmly welcomed by both the existing team and the wider scholarly community during the project’s conference and got stuck straight in with the work. No, I am thinking of men such as Raoul de Vienne, lord of Louppy, who on Thursday, October 9th, 1354 made his first contact with the court of the relatively new regime of King John ‘the Good’ II of France (1319-64, reigned from 1350 to his death). Raoul was by then an experienced courtier, having already served the previous monarch, Philip VI, yet, during the intervening years his services and personal life has been interwoven with the cause of Charles II ‘the Bad’ of Navarre (1332-87, reigned from 1349) during this turbulent period in French political history. Still, upon such first contact, Raoul—as would any aspiring courtier—would have needed to quickly assess the cultural environment of the court. A lack of proficiency in this could easily end up in missed opportunities if not actual trouble for anyone whose career relies at least in part on grace and favour. Tastes and fashions change, and keeping up both with patrons and competitor-courtiers was essential, then as now, in a corporate environment. A celebrated career as, among other responsibilities, governor of the Dauphiné in the 1360s and 70s suggests Raoul’s success in this regard.

It is safe to assume that new arrivals at court did not go through an official induction process. Still, most courtiers would have already been trained, acculturated and active within broadly similar courtly environments. The specific need for assimilation upon arrival, therefore, would not have related to the underlying, systemic elements on which this culture was constructed, but on the subtleties differentiating this court, at this point of time, from any other. We all know how theory and practice differ in social situations, and how thin is the line between standing out and putting your foot in it. In both forming such cultural assessments and projecting their own identities, courtiers such as Raoul would have relied on fleeting, partial, and indeed, accidental exposure to a court’s culture. By the placing of luxury artefacts at the foreground of the courts’ operation, they would have suggested themselves as a primary port of call when making their judgements. In this process, immediately recognizable visual tropes communicating value and identity more efficiently than subtleties of details and their potential interpretations.

As part of my project, I am interested in this kind of exposure: in how we can understand its processes or analyse the effect objects had within this setting. Identifiers of courtly status and uniqueness could be very subtle and wide-ranging. They did not apply only to a court’s visual currency, and within that currency, not only to the kind of objects and visualities I intend to explore. My emphasis on books—and in particular, the sub-set of luxury books containing secular music—is due to their multiple ontologies. Their place in cultural discourse stretches over a wide range of interactions. At different times and contexts, they can be examined for their external material worth, size and craftsmanship; their internal artisanship and presentation; they can be contemplated for their contents on both the single piece and collection level, their technique and their emotional effect; within their content, they often act as commentators on their own cultural context; they can act as a focal point for performance, and as the starting point for debate beyond it. The concentration on music and secularity removes any vestiges of practical need, making their functionality and performativity purely cultural; through the peculiarities of musical notation and the demands of its performance, this also strengthens the performative element of books’ essence, weakening the claim of the private readers; finally, they engage with a further level of professional mediation, both copyists and performers. I hope to get to performance, audibility and close interpretation later on in the project. For now, I limit myself to exploring the effects of presentation, layout, font, and notational technique on the visual impact of such artefacts and the meanings such impact conveyed from the courtier point of view.

Raoul’s example is interesting also in this regard, as not only did he share political interests and a network of patronage with Guillaume and Jean de Machaut, but his name appears as one of very few people to be named within Guillaume’s poetry. As it is often difficult to find evidence of cultural activities even for well documented figures, this link is really intriguing. Machaut’s multiple manuscript-collections of text and music are prime surviving examples of the kind of object I am pursuing. In looking at them, I ask not what they say about Machaut, but about their owners; I do not compare the quality of readings, but the effect of their general presentation. This releases my inquiry from the notion of ‘oeuvre’ or ‘urtext’, making sources usually dismissed as peripheral or partial just as relevant as those associated with the author himself.

Results to be reported in due course!

Uri

Further reading:

Raymond Cazelles, Société politique: noblesse et couronne sous Jean le Bon et Charles V (Librairie Droz, 1982).

Lawrence Earp, Guillaume de Machaut: A Guide to Research (New York: Garland, 1995).

Malcolm Vale, The Princely Court: Medieval Courts and Culture in North-West Europe, 1270-1380 (Oxford, 2001).

Following on from the first post in this series, in which David Murray discussed Pilgrim II’s circles in Avignon, he turns now to the members of Pilgrim’s court once he ascended to the Throne of St Ruprecht and became Archbishop of Salzburg.

Medieval Salzburg sat very much in the middle of things: in terms of secular geography, one might think of it as lying somewhere between Wittelsbach Bavaria and Habsburg Austria (and I wrote in my last blogpost about some of Archbishop Pilgrim’s familial connections with the Habsburgs). Alternatively, in terms of the fourteenth-century Church, Salzburg’s ecclesiastical direct influence extended from the middle of Bavaria, where Freising (near Munich) was the seat of a suffragan bishopric, to the north of modern Italy, where another Salzburg suffragan was Bishop of Brixen. The bishop of Salzburg was also secular lord over much land in Styria, reaching into modern Slovenia. By another measure—as evidenced by Archbishop Pilgrim’s machinations in order to hasten the end of the Great Schism—the city on the Salzach lay in the overlap between the Pope in Avignon (or so Pilgrim said—his Chapter, by contrast, held true to Rome) and the King of Romans in Prague.

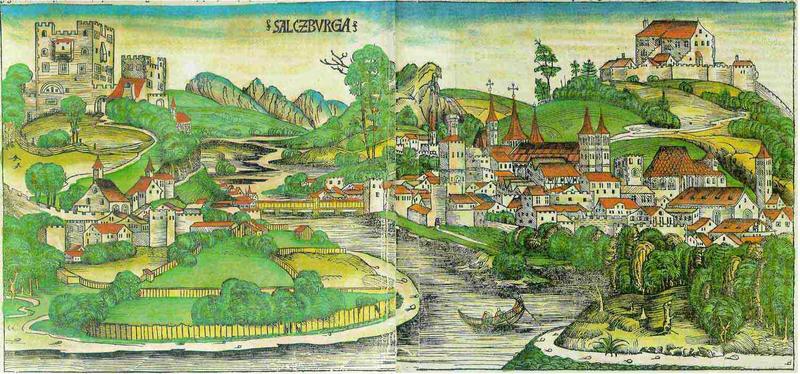

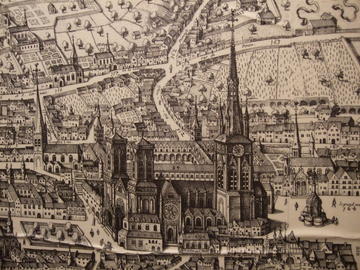

A view of Salzburg from Hartmann Schedel’s Weltchronik of 1493. Now Weimar, Anna-Amalia Bibliothek, Inc. 122

Just as the Hochstift as an institution can be thought of on multiple overlapping maps, so too were the individual courtiers and hangers-on around Pilgrim von Puchheim players in various different spheres. Two instances are particularly illuminating, and not least of all because they are individuals who were particularly close to Pilgrim. The first, Haug von Goldegg, to whom the rest of this post is devoted, was a secular member of the archiespiscopal court. My next post will be focussed on Wilderich de Mitra, Pilgrim’s chancellor and a cleric.

Haug von Goldegg was the last of a dynasty of Salzburg nobles, part of a class whose social position came from long years of service to the archbishops. Though the Goldeggs had come down in the world since their glory days in the early fourteenth century, they remained hereditary butlers to the Archbishop. They were still a force to be reckoned with at the end of the century, and that was all due to salt. Salzburg made much of its money from the production and shipping of salt, essential to the preservation of meat before the advent of the refrigeration, and the Goldeggs were major players. Of the saltworks, four belonged to the archbishop, while others belonged to, or supported, the abbey of St Peter, Nonnberg convent, and cathedral chapter in Salzburg (where Haug’s brother Wulfing had been a canon since the 1350s). The abbeys of Raitenhaslach (Bavaria) and Salmansweiler (Swabia, now better known as Schloss Salem) both had an interest in saltworks near Salzburg. But on their own, the Goldeggs owned five saltworks. It is hardly surprising then, that, when the main line of that family died out in 1400, the jostling of more distant relatives for a piece of this rather savoury pie was enthusiastic.

The Castle and Lake at Goldegg. The present Castle goes back to a fortress built from 1323 by Wulfing, grandfather of Haug and close ally to the earlier Salzburger archbishop Friedrich III von Leibnitz.

Haug was clearly a close associate of Archbishop Pilgrim. It is tempting to put this down to a similar taste for display. For instance, when Pilgrim travelled to meet the dukes of Bavaria in 1387 at the abbey of Raitenhaslach (a meeting, incidentally, that ended with Pilgrim being held hostage by the Bavarians for several months), the two travelled together in some style:

Pilgrim was accompanied by 34 knights and noble pages, partly members of his Council and of the Salzburg Stiftsadel, partly squires of the Hofgesind, his entourage of armed mercenaries. There were also guards, chamberlains and two pipers, then the servants of the noblemen. The most distinguished of Pilgrim’s companions, Sir Haug, the last of the Goldeggs, himself had another four knights and six pages with him. (Klein 1972/73: 50-51; my trans.)

Haug also interacted with other members of Pilgrim’s court. For instance, Pilgrim’s steward Reicher von Rastat re-founded the church of the Virgin at Altenmarkt in the Pongau valley (you can see an earlier post about Reicher and the Virgin here), and following the fourteenth-century devotion to the Holy Family, built a new chapel dedicated to Sts Anne and Achatius, one of the Seven Holy Helpers.

The chapel of Sts Anne and Achatius in the churchyard at Altenmarkt.

Haug von Goldegg, himself closely linked with the Pongau as it was the centre of his family’s lands, is mentioned in a charter of 1398 as giving extensive lands to Reicher’s chapel and the associated confraternity of St Anne in Altenmarkt (Martin 1947: 50). This may well be thought of as an ailing man (as noted already, he died only two years later) who was experiencing extreme financial difficulties at the time, making sure that things were a little better on the other side. The fact that Haug did this by supporting the religious work of Reicher, who, as magister curie oversaw Pilgrim’s extensive domains, is suggestive of his well-connected place in the Archbishop’s circle. Haug’s own indirect religious donations were made to pay for a weekly mass at the church in Goldegg. A charter of 1375 shows them releasing lands to be given by Marchart der Pründlinger to the parish of St. Veit im Pongau, a town around four miles away.

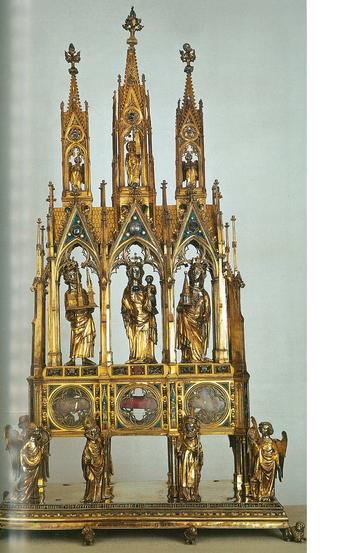

If it is reasonable (and I leave the question open to you…) to judge someone by the company they keep, Haug von Goldegg, last of his dynasty might be thought as the perfect counterpart to Pilgrim. Both were without direct heirs, but nonetheless engaged in the sometimes desperate attempt to shore up or expand their empire. Both of them, although this is hardly unusual in the fourteenth century, took steps to ease their fate after death (Pilgrim established a spectacularly well-endowed chapel next to the Cathedral), and both were given to a certain amount of ceremony as they thought befitting their status.

In my next post, I turn to another figure who seemed to gain Pilgrim’s respect, the doctor in decretis, Wilderich de Mitra.

Further reading

Klein, Herbert, ‘Der Streit um das Erbe der Herren von Goldegg’, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 82/83 (1942/1943), 1–48

Klein, Herbert, ‘Erzbischof Pilgrim II. von Puchheim (1365-1396)’, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 112/113 (1972/1973), 13–71

Martin, Franz, Salzburger Archivberichte 2.2 Politischer Bezirk Bischofshofen, Beihefte zu den Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 2 (Salzburg: Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, 1947)

Schneider, Christian, Hovezuht: Literarische Hofkultur und höfisches Lebensideal um Herzog Albrecht III. von Österreich und Erzbischof Pilgrim II. von Salzburg (1365–1396) (Heidelberg: Winter, 2008)

Vones, Ludwig, Urban V. (1362-1370): Kirchenreform zwischen Kardinalkollegium, Kurie und Klientel, Päpste und Papsttum, 28 (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1998)

In this series of three posts, David Murray writes about some of the connections between his favourite Archbishop of Salzburg, Pilgrim II (r. 1365-1396) and other figures in the medieval Church, as well as some of Pilgrim’s secular allies.

The Puchheims were a well-established family of ministeriales with close ties to Vöcklabruck in Styria, and had long entertained connections with the archbishops of Salzburg. But it was to the Habsburg Dukes of Austria that they owed their allegiance, and so they had re-located to Lower Austria in the thirteenth century to be closer to Vienna. Their devotion to the dynasty was rewarded by being named to the office of Hereditary Steward to the in 1276. (Holders of this office received tribute in the form of pelts from monasteries, whereas towns, amusingly enough, were expected to offer a sturgeon.) They remained distinguished figures on the Austrian scene well into the eighteenth century, when the last of the direct line, Anton, Bishop of Wiener Neustadt, dies in 1718.

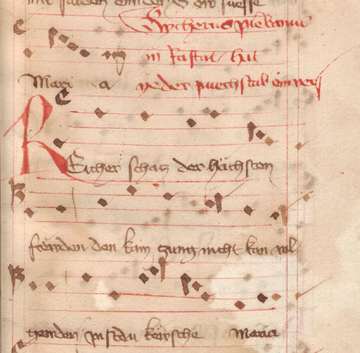

Credit: © Salzburg, Archiv des Erzbistums Salzburg, n. 421 (1372 II 25)

The biography of Pilgrim von Puchheim, who rose to be archbishop of Salzburg, is rather sketchy in its early years. He was probably born in the 1330s, the younger son of Pilgrim IV’s second marriage to Elisabeth von Trautmansdorf. As the younger son of a second marriage, it was perhaps unsurprising that he was destined for the church. By 1353 he was a member of the cathedral chapter of Salzburg (when his brother gave him the revenues coming from lands at Wulffingstein), although he only received priestly orders the following year. The fact that this happened at the hands of Nicola Morosini in Castello, one of the islands of Venice, could indicate that Pilgrim was studying at Padua, renowned for its teaching of canon law.

It is, however, certain that Pilgrim studied canon law at the University of Avignon. This was an unusual choice for someone from the Habsburg lands, as they tended to favour Bologna or Paris, or, later, Prague and Vienna. With the exception of a dispute in the early 1360s about the payment of his canonical income during his studies, the next thing we hear about Pilgrim is when has was named papal chaplain to Urban V in October 1363. After a contested election in 1365, Pilgrim was provided with the archiepiscopate of Salzburg on St Andrew’s Day of the same year.

So there is a long period when we cannot say a great deal for certain about Pilgrim’s activities. Herbert Klein, author of one of the most extensive studies of Pilgrim’s life, names one particular figure as an important protector to Pilgrim during this period. He is Guillaume d’Aigrefeuille the elder, known as the Cardinal of Saragossa. Through him, Pilgrim can be seen making his way into a Limousin faction at Avignon that would colour his politics and diplomatic choices throughout his reign.

Paris, BnF, lat. 11907, ‘Les papiers de Montfaucon’, f. 244.

A 1726 drawing of the tomb of Guillaume d’Aigrefeuille the Elder in St Martial in Limoges